From large manuscript maps to tiny scraps of note papers, there is a wide range of documents in the Chew Family Papers and a variety of conservation procedures for these papers.

One of the least invasive conservation methods for paper is dry cleaning or surface cleaning. Removing the dirt and dust off a document not only improves the appearance of the document, it keeps the hands of researchers clean. Eraser bits and vulcanized rubber sponges are the two products that are used to clean documents at HSP. Extreme care and patience is needed for this process due to the fragility of paper. Attention must be paid to any pencil markings or writing on documents so they are not removed.

The vulcanized rubber sponge is used to clean the linen backing of a manuscript map.

Paper documents are best stored flat. In the Chew collection, many items have been folded or rolled requiring humidification and flattening. Over time, fibers in paper can become stiff and brittle. Humidification helps the fibers in paper to relax. When a folded, crumpled, wrinkled, or rolled document is humidified, it can then be opened with ease and without damage to the paper.

The document is placed in a humidification chamber. The document is then unfolded or unrolled, placed between blotter papers and pellon, and put under weight.

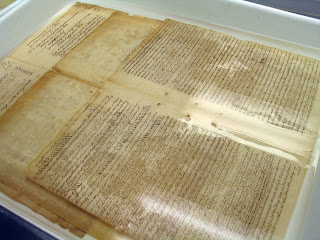

A document is washed to de-acidify and clean the paper. Washing also reconditions the fibers making the paper pliable and malleable. Prior to washing a document, it is necessary to test to see if the ink is water soluble. The document is placed in a bath of deionized water. After twenty minutes, it is carefully removed and placed between blotters and pellons to dry.

Once papers have been cleaning, humidified and/or washed, they are ready for paper mending. HSP only uses wheat paste and Japanese papers for mending. Often the Japanese papers are dyed to match the color of the document using high quality acrylic paints. A thin coating of wheat paste is applied to a strip of Japanese paper. The glued-out strip is carefully placed on the tear, burnished into place and put under weight to dry flat.

Before and during mending. The excess Japanese paper will be trimmed.

6 comments:

That is an amazing process. It makes my archive work look quite boring in comparison! I would love to learn how to preserve paper.

Thanks for posting this fascinating explanation. I particularly enjoyed the picture of the partly-cleaned linen map.

What is "pellon"? My dictionary does not mention it by that name.

Often the Japanese papers are dyed to match the color of the document using high quality acrylic paints.

I don't get it. What's the point of dyeing the contemporary paper?

Mark,

Mainly for aesthetic reasons are the Japanese papers dyed. The majority of Japanese paper used for mends is a very thin variety called tengucho. Tengucho dries with enough transparency for text and imagery to be visible, if it is necessary to mend over such information. Undyed tengucho is white and thus dries in a white haze, which can be rather unsightly on darker shades of aged paper. By dying the Japanese paper to match the paper color of a document, mends are less apparent.

But by making the mends less apparent, aren't you obscuring the history and provenance of the document? Don't you worry that you might be sabotaging some future historian who is trying to figure out something about 18th-century paper?

Mark,

Our main goal in processing and conserving these documents is to make them accessible to researchers and to safeguard them from further damage. While it is true that mending alters the document, if you look closely, you can see the mends. Anyone who is interested in researching 18th century paper would be able to see the process. And there are plenty of documents in the collection that have not been mended.

As these papers are used, tears can become worse from frequent (or even occasional) handling. We want researchers to be able to work with the materials, and Leah's repairs make that possible. If an item is too badly damaged, it becomes unusable, and often unreadable, because of losses in the paper. It's a balancing act between preservation and access, and we try to be as true to the originals as we can while still making the collection available for use.

Post a Comment